The Soft Long Story

Recently, my pen friends showed me an Instagram post in which Samuel Naldi talks about the potential for growth of fountain pens in the luxury market. Naldi talks about the pen industry being where the watch industry was 30 years ago. He expects fountain pen prices to increase dramatically. In a comment to the Instagram post, Naldi wrote, “Now, if writing instrument get explained and marketed in a way better way, the amount of people that will consider will grow in a way that i think we cannot even understand.” This was a controversial post, with mixed reception both from pen enthusiasts and from watch enthusiasts. It was fun to discuss.

I don’t care about ‘luxury” for its own sake. I care about meaning, and histories, and the soft long story. With traditional artistic processes, craftspeople who are very good at their craft often sell their works to affluent patrons, and such patrons’ wealth may create the economic conditions for art that takes a long time to make. In my fantasy novella The Four Profound Weaves, the antagonist is the “Collector” who hoards carpets, but the story itself is about art, and the artists who bring the carpets into the world. They are not making art because of the Collector, even if their works may be bought by him or taken by force. Art can exist in the context of patronage and trade, but it does not only exist because of the economic context. Art is a human need.

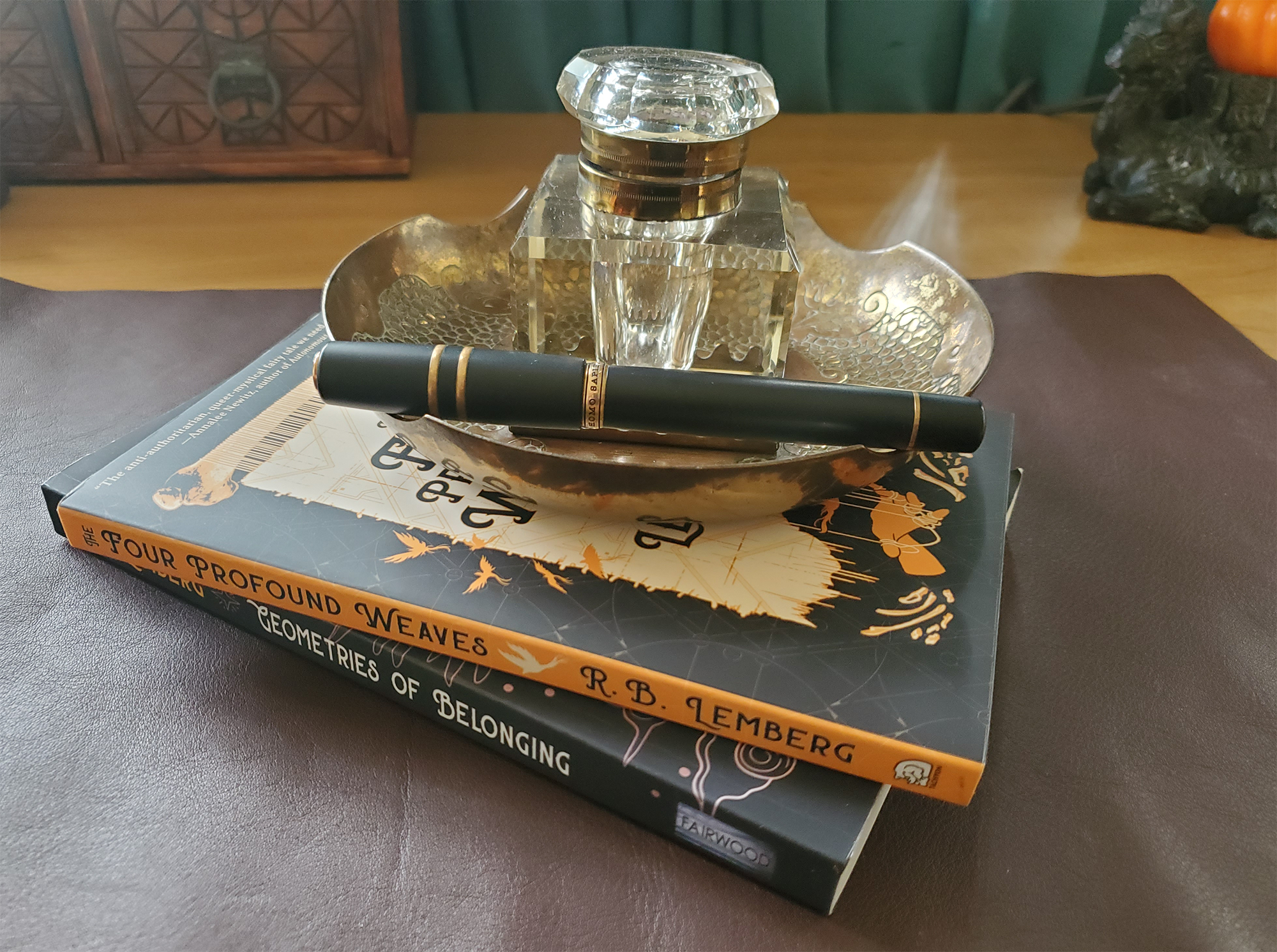

Two fantasy books I wrote, Visconti Homo Sapiens fountain pen (a gift from my mother in law), and an antique inkwell found in Prague (a gift from my mother).

Both fountain pens and watches occupy a space of yearning for a world of earlier mechanical innovation when technology and industrialization went hand in hand with handmade and artistic processes, when pen shops big and small made their own nibs, and watchmakers assembled watches from parts. Such craftspeople had a long apprenticeship, and often dedicated their lives to the careful pursuit of their craft. You could visit such artisans in their shops, often in the same town, not too far away. You could get to know them.

So much of modern technology cuts out the laborious, handcrafted process in favor of quick results. A modern digital watch has been rapidly assembled, often in far-away economies, often with human rights violations involved in the process. Such a watch can tell me how many steps I took and how badly I slept (whether I want it or not). An Apple watch would push texts and take data when I want to simply exist without my steps, breaths, spending habits, health, and productivity being relentlessly measured and sold to advertisers.

A mechanical watch offers a different feeling. Such a watch evokes craftsmanship, years of thoughtful and delicate labor followed by years of involved and caring ownership of this one cherished thing. Such a watch does not spy on you, is not a part of a vast network of corporate data-gathering. You take it off at night. You might want to pass it on to your child.

Reality might be very different, but this is the storytelling framework of a mechanical watch.

Bird detail on the Onoto Keats fountain pen; folk art wooden bowl is from my native city of L’viv, Ukraine. It was originally in use as a beggar bowl.

Those days, AI can generate writing for me, in my own style. But I don’t want that. I developed my own style by hand, through years of writing and publishing, and I don’t care how well AI can mimic that. There’s so much pleasure (and pain) in writing drafts laboriously, thoughtfully, in feeling the emotions of the characters, sinking in the sensory detail of the fantastical worlds I create, connecting meanings, crafting each sentence. I am not a watch person, but I love textiles. I can tell you that no mechanical-woven rug programmed by a computer can replace a carpet hand-woven by makers in a community of makers, from a lineage of centuries. Every detail counts here: the making and spinning of wool, the flowers and grasses gathered to make the dyes, the meaning in the patterns, the ancient trade routes that continue to exist despite thousands of years of calamities. The terrible histories of exploitation, oppression, and wars in which beauty and creativity are embedded. The hand-made carpet is alive - with stories and legacies, with symbolism and loss, with memory and forgetting, in a way that a machine-woven commodity will never be.

Detail: A smallish, hand-woven Persian tree of life rug circa 1920, with birds and deer. I got it from Artifacts in Iowa City. A modern machine-made rug from a big box store would cost about the same.

This is the charm of vintage technologies that have once been new, but have settled into themselves and once again occupy a space which elevates process. These technologies in themselves have acquired stories.

I have recently visited an estate sale in Kansas City. Everything there felt familiar to me - the love that permeated the space, thousands and thousands of books filling the house from attic to basement, one of the owners’ paper marbling studio where she marbled papers for book arts. It was a Jewish home, which is meaningful to me as a Jewish person. In her wonderful essay “What makes a Jewish home Jewish?,” anthropologist Vanessa Ochs writes about Jewish-signifying objects:

“Consider books, some of which might be by Jews or about Judaism–but also all books in abundance, filling shelves, piled on floors, spilling off of tables, scattered in children’s rooms.”

An abundance of books is not unique to Jewish homes, but it is definitely a thing in Jewish homes. In ours, certainly - for me, books don’t count as collections or possessions - books simply are. They are friends, companions, comfort, a source of solace and knowledge. Books are memory, reflecting our lives. Books are love and loss and longing.

Back at the estate sale, we purchased many books, but now I think I should have bought even more; I left behind a small embroidery and I regret letting it go. I did buy a painting.

Hand-marbled paper, by Elinor Eisemann.

I’ve traveled sideways from stationery in this essay. When I was planning it, I was going to say that writing culture is for everyone, while luxury watches are not; fountain pens run the gamut from very cheap to very expensive, while modern craft watches are beyond the reach of most people; but maybe none of this matters.

I don’t care if fountain pens are about to become a luxury commodity. I am here for the slower and more careful world. I always want an in-house nib. I would love to own an Opus Cineris nib one day, which is entirely handmade by Annabelle Hiller. I created handbound books for many years, and I admire the craft of great bookmaking artisans. The idea that each Italic nib from Aurora is hand-processed excites me. But I find that a modern Montblanc pen does very little for me, even though it commands a luxury price. I care about story and intricacy, and the pleasure of using an older technology. Writing itself is a very old technology, but it, too, is new in the grand scheme of things. Five thousand years of writing is a soft foam floating on the vast deep sea of storytelling which existed for aeons before writing began. Whether I’m writing or not, I feel the pull of that tide.